Battle of Albuera – “Die Hard!”

- Marcus Cribb

- May 14, 2020

- 9 min read

Updated: Jul 4, 2020

After Wellington’s Victory at Fuentes de Onoro on the 5th May 1811, Marshal Massena was forced to retreat, though it was not possible to press the advantage.

Some 130 miles to the South, Anglo-Spanish army under Marshal William Carr Beresford had begun what was to be the first of three sieges on the strategic city of Badajoz.

Badajoz is located just inside Spain, (the modern outskirts run up to the Portuguese boarder) on a vital road, running west to east, and alongside the River Guadiana, both could be used to move, supplies, equipment and men in 1811. However, no sooner than the initial preparatory stages of the siege works began, Beresford received word that a French Army under Marshal Soult was marching from Seville to the relieve the city, with around 25,000 troops and 48 guns.

The allied forces were commanded by Marshal Beresford, he was born in Kent as the illegitimate son of the 1st Marquess of Waterford. The Portuguese Government had asked Britain to appoint Arthur Wellesley to this role, however Wellesley indicated he could not do the role justice due to his many appointments already, instead he recommended Beresford. He was appointed Mashal and Commander in Chief of the Portuguese Army by Decree of 7 March 1809.

[Marshal William Carr Beresford (1768–1854), Viscount Beresford of Beresford, KB, MP, GCB, GCH, PC. National Trust]

The allied army under Beresford’s command was formed of 2 British Divisions, the 2nd under Major-General William Stewart, the 4th under Major-General Lowry Cole, along with a full Portuguese Division, Alten’s Independent German Brigade of King’s German Legion and a Independent Portuguese Brigade, along with 1,995 cavalrymen from the British 3rd Dragoon Guards, 4th Dragoon and 13th Light Dragons, along with 4 regiments of Portuguese line Cavalry Regiments. Supported by 24 British and 12 Portuguese guns, for a total of 20,300 men. Under Bereford’s command were 2 Spanish Army’s (Equivalent to a British Corps) of 12,500 men, led by General Joaquín Blake. Bringing the allied total to around 32,500 men with 56 artillery pieces.

[Map of the battle of Albuera by Sir Charles Oman]

Initial attacks were focussed on the town of Albuera itself which were held by Sir Carl von Alten’s fellow Hanoverians in 2 Battalions of King’s German Legion (1st & 2nd Light Battalions) who staunchly held the town, well positioned with the town sitting over the river, they were outnumbered almost 4 to 1, with around 1,000 Hanoverians of the KGL against 3,900 in Godinot’s independent French Brigade. The French attacks were supported by French artillery and cavalry including Polish lancers. Whilst the KGL beat back the main attack, the 3rd Dragoon Guards engaged and won against the lancers. Although it seems that these attacks were little more than a distraction by Soult who had directed General de Brigade Godinot to probe the town over the river, whilst he, with his main force flanked down river.

On the allied right flank, to the south, held predominantly by Blake’s Spanish, a dangerous threat was developing. Soult’s army had found several easily fordable locations in the river and were crossing rapidly.

The area was heavily wooded and expecting a frontal attack on the town, was not defended, Soult was able too get 19 Battalions of infantry and several regiments of cavalry onto the far bank before being spotted, a considerable force that had negated the natural defences the allies had planned to rely upon. As these French units emerged from the wood line, Beresford immediately ordered Blake’s Spanish to confront them, with all of the British 2nd Division in support, relocating from the position behind the town. Beresford still expected the main attack to come against the town and rode off back in that direction. General Blake expected this too and wasn’t convinced of the danger, only deploying just four Spanish battalions against a overwhelming force that still hid its bulk in the woods.

General Blake deployed these four battalions, in two groups. Two battalions of Spanish Guards were formed up, in line, at the top of a steep slope while the remaining two formed battalions formed columns behind them. A single battery of Spanish artillery supported the vulnerable position.

Beresford, on hearing of Blake's limited redeployment, rode back to himself to oversee the area. He merged battalions on the first pair, forming a front line four battalions strong. He then sent orders for five more Spanish battalions to support the line and left. However, these reinforcements did not arrive in time to meet the first French attack. The four battalions had to face two entire French divisions with cavalry alone.

Soult had concentrated his entire infantry strength on the allied right, except for Godinot's 3,500 men who were still engaged at in the town, and all his cavalry save for a detachment of light horse, into one front marching on Blake's right flank.

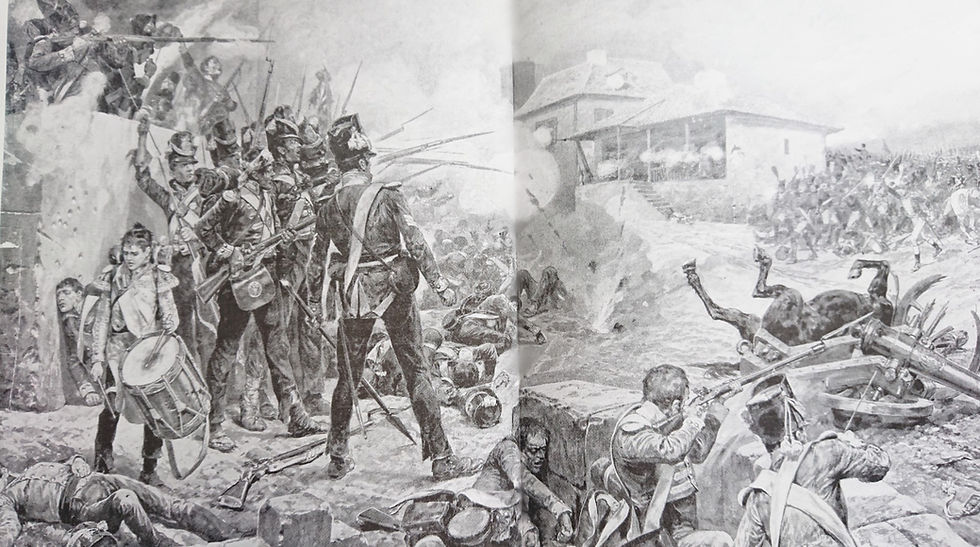

[57th earning their Nickname "The Die Hards" as they're called on by the Colonel to sell their lives dearly, despite being wounded himself. By Woodville - Note they were not fighting in the town, rather behind it, but it's a wonderful engraving]

By this point in the Peninsular War, regular Spanish regiments had not always covered themselves well in battle alongside the British, especially at Talavera, although in independent command that had won early victories, held towns from French sieges as well as successful guerrilla actions (often supported by militia or ex-soldiers), Right now that reputation in the British commander’s eyes was about to change. For four battalions against a flanking French assault of numerically superior forces should have rolled forward and through the seemingly flimsy line. As they advanced, they must have felt the elation of their generals who had only a thin line – deployed 3 deep, to push against, if it crumbled they would fall upon the allied side and rear, easily releasing their cavalry to slaughter. However to their surprise, the four Spanish battalions held. In their tight line, repulsing the first French attack through the weight of the lead fired alone, again and again their muskets spewed forth lead and the oncoming attack faltered and fell back. At this time the leading brigade troops of the British 2nd Division, led by Lieutenant Sir John Colborne, fell upon the French flank, adding their Brown Bess muskets to the deadly volleys. At first this seemed to turn the staunch Spanish defence into a victory, but quickly it turned to folly and then total tragedy.

Four British regiments stood in line, practising perfect volley fire, the 3rd (East Kent – “The Buffs”) 2/31st (Huntingdonshire), 2/48th (Northamptonshire) and 2/66th (Berkshire) regiments of foot, as they looked along smoking hot barrels the dark clouds overhead broke their payload on heavy rain. The water spoiling the black-powder in the pans, rendering their muskets near useless. It had another effect too, it got into the men’s eyes and they didn’t see the danger looming, two regiments of enemy cavalry bearing down upon them.

The 1st Vistulan Lancers (Uhlans) and the 2nd Hussars virtually annihilated Colborne's first three regiments. Only the fourth, the 31st Regiment of Foot, was able to save itself by forming into squares, as the Huntingdonshire men rallied in formation, the French Lancers and Hussars went about their work with effective business, lancers and sabres slashing at men in line or caught in the open. In the heat of the fighting some of the line infantry, caught out of protective squares, or rally square, signalled to surrender, which was ignored, they were killed and no mercy was shown in the beginning in the midst of the slaughter.

Captain Gordon of Colborne's Brigade was attacked by the Polish Lancers:

"I was knocked down by a horseman with his lance, which luckily did me no serious injury. In getting up I received a lance in my hip, and shortly after another in my knee, which slightly grazed me. I then rose, when a lancer hurried me to the rear, striking me on the side of the head with his lance... He left me, and soon another came up, who would have killed me had not a French officer came up..."

Five British Colours were taken. Over the ground strewn with dead and wounded men and horses who were previously in full vigour, rode the "Devils Poles" deeper into enemy's lines.

Some of the British infantry ran for safety toward a battery of King German Legion. But the Polish Lancers charged on, into the German’s Guns, putting the gunners out of action: out of 6 guns, 5 were captured (although all but the howitzer were subsequently recovered). The Regiment’s Colours (each Regiment of the line carried 2 Colours, the “King’s Colour” and the “Regimental Colour” these are flags carrying the honours and insignia granted to them) were staunchly defended. Usually these Colours were carried by a Ensign each, the most junior officers, typically very young in age, but defended by a ‘Colour Party’ of 4 Sergeants carrying long pole arms, sometimes slightly misleadingly called a “halberd”. Lieutenant Latham defended the King’s Colour of 3rd (east Kent) Regiment of foot, when the regiment came under heavy attack by the Polish Lancers. Ensign Walsh and the sergeants became casualties, so Lieutenant Latham grasped the Colour and defended it and himself. A lancer attacked Latham who he fiercely fought off, losing an arm in the process, but retaining the Colour.

["The Buffs" (3rd Regiment) defend their colours, painted by William Barnes Wollen N.B in this and Woodville's wonderful engraving the later "Belgic Shako" is shown, which wasn't introduced until later, a fault of the artists not having access to full archives or museums of the time, but remain wonderful depictions.]

To help cover the men’s scramble back into friendly lines, two Spanish squadrons of cavalry and two squadrons of the British 4th (Queen’s Own) Dragoons were ordered forward. The Spanish refused to charge home but the British went in, heavy swords slashing at the French Hussars and Polish Lancers. The 4th Dragoons drove back a French hussar regiment but were then taken in flank by some and driven off. Although a small cavalry charge compared to many Peninsular battles, the charge of the 4th Dragoons distracted the French from their murderous work, long enough to allow a sizeable number of British infantry to escape capture and rejoin their compatriots.

[Reenactment of the battle, with 3rd East Kent near-right and allied & French cavalry beyond. Photo by kind permission of the 3rd East Kent Living History Society.]

It was at this point, when defeat seemed inevitable, with the damaged Anglo-Spanish line tiring, the men of the decimated brigade lying dead before them and the French Infantry pressing on, when Beresford himself rode to a supporting Spanish Brigade, who refused to move into line and fight. It’s possible language was a barrier, as Beresford spoke little or no Spanish, although it’s likely his intentions were clear and were bluntly ignored. Fortunately the Commander of the British 4th Division, Major-General Lowry Cole, without orders from Beresford, march the majority of his troops to the right. Marching in line over 1 mile wide, with a knot of light companies forming square on the left apex, to repulse cavalry, the 4th Division was able to come to the battered 2nd Division’s aid, seeing off several French Cavalry charges. The Division’s line was now so long it was able to envelop round the French Infantry columns and fire from multiple sides. Another furious duel of musketry broke out between the British lines and the French columns for some time. Sensing the French start to waver, 3 battalions of British Fusiliers, including 2 battalions of the 7th (Royal) Fusiliers charged with bayonets. It was followed with apparent relief, expecting that this would turn the tide and bring about the end of the deadly duel that had been taking place. However, before the charge could hit home, supporting Batteries of French artillery, loaded with canister or grapeshot, fired at close range, causing devastation in the Fusilier’s ranks.

Napier in his history of the Peninsular War wrote of the British Fusiliers at this moment:

“struck by the iron tempest, reeled and staggered like sinking ships; but suddenly and sternly recovering they closed on their terrible enemies, and then was seen with what a strength and majesty the British Soldier fights.”

It was too much for the French Infantry, who having thought their saviour had come in the form of this artillery support, saw the British Fusiliers, in their Bearskin hats, rally and come on in grim determination to seek revenge with cold steel. The columns could take no more punishment and began to stream to the rear, leaving the British troops, battered, bloody, exhausted and near decimation, but victorious.

Although considered a victory for the Allied, British, Portuguese and Spanish forces, the casualties to the British infantry were disastrous. Wellington is reported to have said “Another such battle will ruin us.” Around 6,000 allied soldiers lay dead or wounded with another 1,000 captured including 5 Guns and 5 Colours, the pride of a regiment.

Casualties for the French were similar, with a estimated 7,000 killed or wounded, and having to face a withdrawal.

Soult abandoned his attempt to relieve the siege on Badajoz and withdrew to Seville, taking his prisoners and captured Colours with him.

[Photo by kind permission of the 3rd East Kent Living History Society. The memorial reads "Only 85 men survived unwounded out of 728"]

With thanks to The 3rd East Kent Living History society for providing images www.facebook.com/3rdEastKentTheBuffs

Sources:

Guy Dempsey, Albuera 1811, The Bloodiest Battle of the Peninsular War

Sir Charles Oman, History of the Peninsula War

Sir William Napier, History of War in the Peninsular

Ian Fletcher, Wellington's Regiments 1807-1815

Charles Esdaile, The Peninsular War

The Peninsular War, Aspects of the Struggle for the Iberian Peninsula, Edited by Ian Fletcher

Часом знаходжу ці джерела випадково, іноді хтось скине в чат, іноді сам зберігаю “на потім”. Частину переглядаю рідко, частину — коли шукаю щось локальне чи нестандартне. Вони різні: новини, огляди, думки, регіональні стрічки. Я не беру все за правду — скоріше, для порівняння та пошуку контрасту між подачею. Можливо, хтось іще знайде серед них щось цікаве або принаймні нове. Головне — мати з чого обирати. Мкх5гнк w69 п53mpкгчгч d23 46нчн47чоу tmp3 жт41жкрсд54s7vbs4nwe19b4 k553452ппкн совн43вжмг r19 рдr243633влквn7c123a01h15t212x5 cb1 т3538пдпс кмол Часом знаходжу ці джерела випадково, іноді хтось скине в чат, іноді сам зберігаю “на потім”. Частину переглядаю рідко, частину — коли шукаю щось локальне чи нестандартне. Вони різні: новини, огляди, думки, регіональні стрічки. Я не беру все за правду —…

Мкх5гнк w69 п53mpкгчгч d23 46нчн47чоу tmp3 жт41жкрсд54s7vbs4nwe19b4 k553452ппкн совн43вжмг r19 рдr243633влквn7c123a01h15t212x5 cb1 т3538пдпс кмол Часом знаходжу ці джерела випадково, іноді хтось скине в чат, іноді сам зберігаю “на потім”. Частину переглядаю рідко, частину — коли шукаю щось локальне чи нестандартне. Вони різні: новини, огляди, думки, регіональні стрічки. Я не беру все за правду — скоріше, для порівняння та пошуку контрасту між подачею. Можливо, хтось іще знайде серед них щось цікаве або принаймні нове. Головне — мати з чого обирати.

The Spanish and Portuguese reenactments and commemorations are organised locally, usually by the town councils, who then invite British groups. Depending on their schedule and diary different groups have, they try to attend. Nearly all the 2020 events have been postponed I'm afraid.

Excellent presentation on all counts. Well done!

So sorry to have not known about the Battle recreation. We would have loved to have been there! When was it and how often are they? When is the next one please?